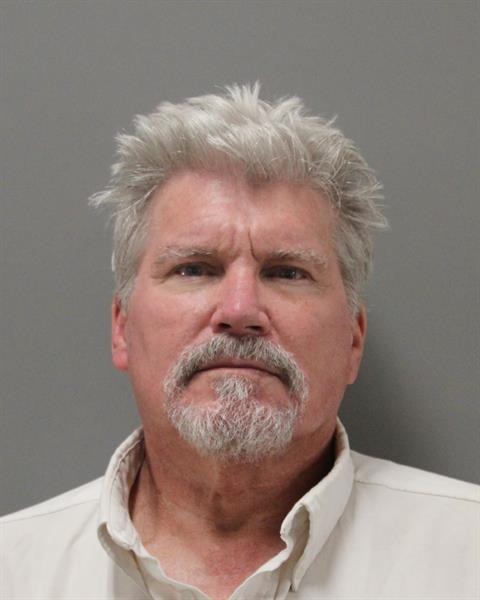

Guest Opinion by Dave Erlanson Sr. of Bonneville County

In Part I, we delved into the source of authority over water by looking at four founding documents. Now we must discuss laws passed by Congress concerning water control authorities and usage applicability to various factions that would be affected by these Federal laws. If, in fact, they have justifiable authority to make laws concerning the waters of the United States (WOTUS) in the first place. There are numerous laws disposing of the waters, the ones below are a few examples.

The Submerged Land Act (SLA) of 1953 is the federal law that reaffirms and recognizes the title of submerged lands and waters flowing over them to the States. This applies to the “navigable waters,” where under the Commerce clause of the United States Constitution gives the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authority, regardless of the SLA and Congress’ intent. Here is where I contend that federal overreach of authority has occurred. Let’s look a bit closer. The definition of navigable waters in Section 502 (7) of the Clean Water Act (CLA) of 1972, “The term ‘navigable water’ means the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.” If this is the true definition of WOTUS and its inclusion that all waters are deemed navigable, then under the Northwest Ordinance (NWO), all waters are free and open to use without any impairment, permits, duties, taxes, etcetera. Under the SLA, 43 US Code §1311(a) denotes that authority and jurisdiction is given to the States “confirmation and establishment of title and ownership of lands and resources; their management, administration, leasing, development, and use.” Further affirmation of State control is located in SLA (3)(e) where it clearly states that a State on or westward of the 98th meridian has control (jurisdiction) over ground and surface waters and that there can be no Federal intervention pertaining to such.

Another federal law of extreme importance is the Act of July 23, 1955 – Surface Resources Act (also found under Public Law 84-167). This Act specializes on the waters flowing through unpatented Federal Mining Claims, of which I hold several. Being a Federal Entity, one can logically conclude that the area in question must be on Federal Property. Although National Recreation Areas “may” contain grandfathered claims, this discussion pertains to reservations/properties controlled by the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management and the thousands of unpatented mining claims within these federal holdings. Under Section 4(b) of the Surface Resources Act it states, “Provided further, that nothing in this Act shall be construed as affecting or intended to affect or in any way interfere with or modify the laws of the States which lie wholly or in part westward of the ninety-eight meridian relating to the ownership, control, appropriation, use, and distribution of ground or surface waters within any unpatented mining claim.”

To recap this discussion before continuing, let’s see what factual evidence we discovered concerning jurisdiction over State waters:

- The Articles of Confederation did not address water specifically.

- The Northwest Ordinance addressed navigable waters only, leaving them free from any impairment of use by the inhabitants of the territories or the citizens of the would be States.

- The Declaration of Independence provides for unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, which none are attainable without water that sustains one’s life.

- We discussed two laws that give control, in all aspects, to the States other than power production, navigation, or flood control, in which the United States retains authority (43 US Code §1311(d)). There are numerous other regulations and laws.

- The Tenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” This is similar verbiage to Article II of the Articles of Confederation. Paramount to our discussion is that the five letter word, water, is not mentioned in either the Articles of Confederation or our present-day United States Constitution, therefore it seems to me to be obvious that the Federal Government enjoys no power over WOTUS within the respective States, specifically westward of the 98th meridian.

With these facts in mind, I leave it to the reader to decide who he or she thinks controls the water at this juncture in our discussion.

Continuing on, within the July 23, 1955 – Surface Resources Act, I’ve mentioned two Federal agencies charged with administration of Federal land, those are the US Forest Service (USFS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM). These agencies administer 650 million acres of property within the United States, situated to varying degrees within the States, with over half being located in Alaska and the remainder being located mainly in the Western States. Here we continue discussing water and under whose authority – States versus Federal agencies.

A document entitled, “Inventory Report of Jurisdictional Status of Federal Areas Within the States (as of June 30,1962),” will unmask not only who has administrative jurisdiction over the water, but I assert, the property itself. Included in this expansive document, which was started under the Eisenhower Administration, one can find the State of Idaho’s listing. Here each USFS holding reservation is listed along with the BLM including the date of promulgation, the amount of acreage included, and a very important number. An example: The Clearwater National Forest shows that it was founded in 1897 and contains 1,676,753 acres; it also has this very important number which addresses its jurisdictional authority to administer these lands. Here it is listed as number four (4), as it is with all USFS and BLM holdings within the geographic borders of the State of Idaho. This is of paramount importance, as it denotes the category of jurisdiction permissible to be employed by the USFS and BLM in their administrative capacity.

Let me briefly explain to you these categories of jurisdiction:

- Category 1: Exclusive legislative jurisdiction is applied when the Federal Government possesses “all” authority.

- Category 2: Concurrent legislative jurisdiction is where the State concerned has reserved to itself the right to exercise authority with the United States.

- Category 3: Partial legislative jurisdiction is the term applied where the State has more rights than merely serving up civil or criminal processes, but has additional authorities also.

- Category 4: Proprietorial interest only (USFS and BLM properties in Idaho) is the term applied to those instances where the Federal Government has acquired some right or title to an area within a State, but has not obtained any measure of the State’s authority over the area.

In other words, folks, the Federal Government cannot regulate or make laws and regulations above its authority (Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2). Simply stated, the Federal Government has the administrative jurisdiction to protect its property, as would any landowner in the United States. However, this does not include making rules and regulations over water usage, wildlife, fish, or aesthetic concerns which could arise on their respective reservations/properties (see United States vs. New Mexico 438 U.S. 696, 1978).

This case is the centerpiece of my Federal Court case to restore the rights of Idahoans to use the waters without enforcement processes being leveled against them by the two aforementioned Federal agencies who have systematically, and unlawfully, commandeered their administrative authority over Idaho’s most precious resource, the water. It is now up to the reader to decide – with the factual evidence presented – who actually owns the water?

To further this discussion, we will review some case law, which is expansive in nature, in a future article.

Readers are welcome to gain additional information by following my two cases:

- Dave Erlanson vs. USFS and BLM, #4:24-CV-00023 BLW.

- David Erlanson Sr. vs. Environment Protection Agency, writ of mandamus to SCOTUS, case number 23-949, in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, case number 22-35894.

As I am a pro se litigant in both actions listed above, any involvement via a pro bono attorney would be much appreciated, as with any comments or factual information. You can contact me through this media outlet.